International Trade and Global Value Chain-Hypothesis and Implications

Turning quick growth pitfalls into opportunities

April 23, 2019

Industry 4.0 consulting: Digitizing the Life Science sector

May 31, 2019Over the last two decades, trade and production have become increasingly organized around what is commonly referred to as global value chains (GVC) or global supply chains. The advances in information and transportation technologies as well as falling trade barriers have allowed firms to unbundle production into tasks performed at different locations to take advantage of different factor costs. Such production fragmentation means that intermediate goods and services cross borders several times along the chain, often passing through many countries more than once. These complex global production arrangements have changed the nature of trade.

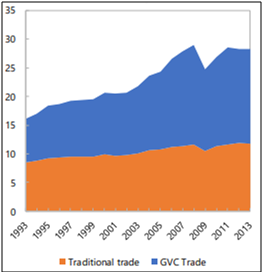

Source: IMF’s calculations based on Eora database. Traditional trade comprises exports of goods and services that are produced in one country and absorbed in the destination

Today, 70% of international trade involves a variety of transactions where services, raw materials, parts and components are exchanged in global value chains (GVCs) across countries, before being incorporated into final products that are shipped to consumers all over the world.

Participation in GVCs has a positive impact on income per capita, as well as its components, investment and productivity. Importantly, we find that these gains are related to GVC trade and not to conventional trade. The results appear robust to endogeneity and reverse causality. The gains from GVC participation, however, are not automatic. There is large degree of heterogeneity. The upper-middle and high-income countries appear to be benefiting from such participation, while we find less robust effects for low and lower-middle income countries. The relationship between upstreamness in GVCs and economic development is not straightforward. While financial and business services tend to be upstream and high in value-added, the link is less clear in manufacturing.“Moving up” to more high-tech sectors as a result of participation in major supply chains does take place but is not universal, suggesting that gains are likely conditional on other factors.

Global production networks rely on the logistics chain, which requires efficient network infrastructure and complementary services. Trade flows in value added terms reveal that transport, logistics, finance, communication, and other business and professional services play a significant role in exports of goods. More efficient service sectors enhance the competitiveness of manufacturing firms.

Domestic firms can only seize export opportunities if they have access to imports of world-class goods and services inputs. Imports help firms to become more productive and competitive in their export markets. Responses to this reality can be undertaken unilaterally and have indeed led to unilateral liberalisation in recent years, but trade agreements allow countries to create disciplines collectively and to address some of the externalities related to activities of firms in GVCs.

Trade agreements should cover as many dimensions of GVCs as possible, from customs barriers to rules of origin to trade facilitation to services. Because there are network and scale effects in GVCs, the gains and the success of agreements in implementing disciplines will be greater when more countries participate, and markets are opened on a multilateral basis. GVCs strengthen the economic case for advancing negotiations at the multilateral level, as barriers between third countries upstream or downstream matter as much as barriers put in place by direct trade partners and are best addressed together. While multilateral agreements are widely accepted as the best way forward, most of the liberalisation outside of purely unilateral opening has occurred at the regional level in the past two decades.

Macroeconomic Implications

In the global supply chain export and import between participating countries add to economic benefits domestically and fundamentally. For instance, final commodities in the value chain formed as a result of trade between nations would typically lead to lower cost of products. Likewise, based on the product category, input costs might be low, labour intensive countries would have higher labour demand for such type of products, etc.

Effects on Economic Activities and Inflation Levels

At a macro level, GVCs magnify the transmission of macroeconomic shocks across countries, weaken exchange rate effects, and widen the benefits of regional agreements. International input–output linkages also create strong links in the formation of prices, implying that inflation in one country is more likely to spill over to direct and indirect trade partners. Such linkages account for an estimated half of the global component of Producer Price Index inflation. GVC participation will be associated with a rising synchronization of real economic activity and inflation across countries. With complex interconnections in production, the consequences of a currency movement for export volumes are likely to be reduced and will become harder to predict. Because exports require imports, and because some exports are processed abroad and re-imported back, a depreciation may not stimulate exports as much as in the past. For example, some recent episodes of significant exchange rate movements, such as those in Japan (2012–14) and the United Kingdom (2007–09), were not associated with very large movements in trade volumes.

Effects on Regional Trade Agreements

The rise of GVCs changes the effects regional trade agreements and how policy makers should think about the possible diversion of trade flows. When firm-to-firm relationships are rigid, the benefits of accessing new markets can be shared throughout the production chains. Forming a regional trade agreement usually leads to an increase in trade flows within the bloc forming the agreement and is also associated with a reduction of trade with partners outside the bloc. Economists call the latter effect a “trade diversion,” because forming an agreement “diverts” trade toward members of the agreement.

Impact on Job Creation

GVCs are significant vehicles of job creation, employing around 17 million people worldwide and carrying a share of 60 percent of global trade. Simply put, GVCs include all of the people and activities involved in the production of a good or service when the different stages of the production process are located across different countries and geographies. As globalization increases, GVCs are becoming more relevant in international production, trade, and investments. And Global Value Chains also have an important effect on job creation.

However, there is a potential trade-off between increasing competitiveness and job creation, and the exact nature of positive labour market outcomes depends on several parameters. Given the cross-border (and, therefore, multiple jurisdictive) nature of GVCs, national policy choices to strengthen positive labour outcomes are important yet limited. By structural transformation and generating new linkages in and around the chain, further creation of jobs take place.

Having said this, the eventual outcome on the labour market depends on several factors, including the readiness of the domestic labour force to respond to changing global demand, and flexibility of labour market policy to allow for ease of labour mobility.

Conclusion

Thus, global value chain and international trade together serve a broader dimension to countries and industries wherein their participation will lead to wider implications for markets domestically and internationally. Owing to the presence of GVC, trade liberalization leads to increased skill premium between countries. When trade is liberalized, countries specialize in their comparative advantage stages, and these specialization patterns, in conjunction with usual sectoral specialization, lead to increase in skill premium. In this manner, several implications of integration of trade and global value chain can be outlined with the expansion of supply chain across countries. Diversification of trade and its close linkage with development of any supply chain is therefore a key focus dimension for industries and countries, which in next steps, could further be broken down into granular levels of sectors and products, and so on.

Our highlight thus remains on the integration of closely related sectors of the industries and its shaping up in the global chain. In the next few articles we will continue to focus on such developments.